When you prop up a child, you take away the chance to develop balance and posture naturally.

Your Child learns by moving in her world, on her own. Don’t drag her to “teach” her to walk.

Let her stand, get her balance, and move when she’s ready. Same with sitting. She’ll do it perfectly, when she’s mastered the prerequisites. There is no benefit to “Sooner.” There can be harm in attempting something before you’re ready to.

Your child needs space to move freely on his own. Watch him add capacities when he is in control. When children move freely, they get strength and balance. There is no rush. Confidence grows within as the child masters the world she’s in, which she does without your direct help. You support her by building and maintaining that world she is in, and then paying attention (without praise or judgement!).

Often, you can see discomfort in both the body language and faces of children who don’t have free control of their own bodies. You can see it on the street, and you can see it in unlicensed photographs from the web. To me, the kid pushed into plastic thing at the top of the page is cruel. The photo at left isn’t as awful as it can be, but one must always ask: “What is that like for the kid?” And the other picture, from an article actually called “teaching your baby to sit,” has the kid’s legs folded into in a position that I don’t believe she could arrive at by herself.

free control of their own bodies. You can see it on the street, and you can see it in unlicensed photographs from the web. To me, the kid pushed into plastic thing at the top of the page is cruel. The photo at left isn’t as awful as it can be, but one must always ask: “What is that like for the kid?” And the other picture, from an article actually called “teaching your baby to sit,” has the kid’s legs folded into in a position that I don’t believe she could arrive at by herself.

How the baby learns to stand and walk … and what that teaches us about parents.

See (or remember) your baby’s big muscles learning to work together, starting from the inside – the core rocks with timing, coordinating that heavy head with limb kicks – eventually, they flump over onto their side. Each step has its challenges, joys and fears; each attempt is an experiment. Each step builds confidence, and the mechanics build naturally on the skills and strengths developed during the previous steps. It’s the amazing system that’s worked for everything in the natural world forever.

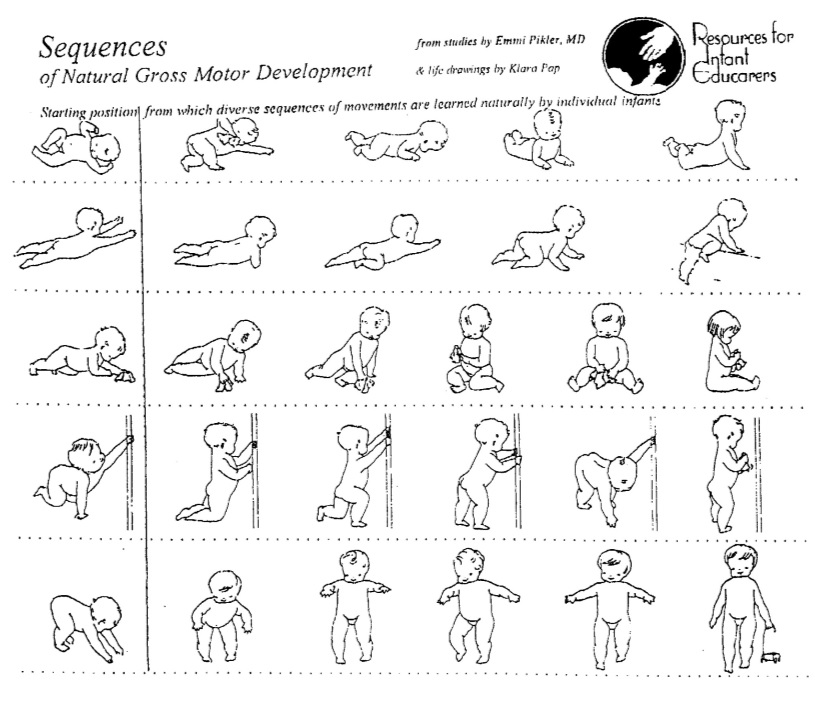

Step by step, your child will roll, half sit, sit on its butt, get up, and walk. At Loczy, Emmi Pikler worked with her associate Klara Pap in creating these wonderful drawings of the natural progression of the handful of months in which a child learns to walk: So, please enjoy the profound pleasure of watching this miraculous, beautiful and pretty-much inevitable voyage … as your child moves on their own, ultimately making a brief stop at walking before stage-diving off sofas, scaling fences, etc.

So, please enjoy the profound pleasure of watching this miraculous, beautiful and pretty-much inevitable voyage … as your child moves on their own, ultimately making a brief stop at walking before stage-diving off sofas, scaling fences, etc.

What does this have to do with parent behavior?

What happens when parents “help” their kids learn how to walk? Let’s say the squares on Pikler’s chart were numbered, 1 – 25. In effect, the parent is saying “Hey, I see you are at stage 17, starting to pull yourself up. I am going to drag you, arms over head, past the next 8 steps, to #24, which I will ask you to do with your arms held above your head.”

Take a moment to imagine the child’s experience – or even to remember your own. What does it feel like to learn to balance?

Eventually, the kid will get to step 18, which has to come before 19 and 20, etc, if he is to eventually walks on his own. That kid who is “helped” by being dragged may not get to any steps any sooner, won’t have the advantages of balance built from the ground up, and is more like to arrive with anxiety than with confidence, thanks to the “help” and the “teaching.”

We parents love our kids, and it feels natural to want to “help” and “teach” our young children – we know they are special, and we can’t help but try to advance them, when it might be better to just step back and pay attention. So, this is another case of where parent or grandparent need (in this case, to “help”)can override the child’s need (to take the time to develop the self-knowledge and confidence that come from mastery, as well as their bodies getting the right skills and strengths in the right order.

(Quick Time Out – re: Tummy Time. Tummy Time is Torture. Tummy Time is Trauma. A child allowed to lie freely on her back, allowed free movement to kick and do crunches and roll – as in Dr. Pikler’s chart, above – has exactly the strength and development program they need. A child allowed free movement does not need to be “accelerated” into a position they aren’t ready for. Imagine the child’s experience. Look at a baby’s face when they are flipped over like that – it’s cruel. It might make sense for babies who are not allowed free movement – and, sadly, many are restrained for much of the day. It’s worth discussing with your pediatrician – everyone might learn something!)

Back to Parents and “Helping” – This is where knowing a bit about habits can help us – the instinct is to help is legit – evolution makes it feel good to make our love real through the action of helping. But what do we do when what feels right to us is not best for them? (The converse is true, too: what’s good for them can be so painful for us: seeing them frustrated, seeing them learn from mistakes, accepting their need for distance and separation as they grow older, etc). I will write about how habits can be managed in more detail elsewhere (I bash them here), but the short direction is this: Turn Down your habit response to the cues that make you offer help – and teach yourself to see, and respond to the same events by seeing them as a different cue. Tune In to the cue of seeing your child learning – and then develop the habit response of stopping to enjoy watching learning happen. So instead of “He’s hit an obstacle, he needs my help” you say “He’s hit an obstacle – time for some learning.”

This issue of parent evolves as kids age, but the same principles apply right up through dating and job missteps. Once again, this is the time – our kid’s learning, and our instincts and responses, are in a tangible world where challenges are simple and visible, rather than, say, adolescent social life, or invisible toddler drama -but when it’s standing, sitting, etc it is easy to see. So, just as all of the types of learning and development are connected for the child, I believe much on the mental side of parenting is connected, in part because as our kids change rapidly, we pretty much stay the same – our “Parenting Mode” is pretty consistent. This is yet another reason the early years are such a great opportunity: the learning window of the first three years is irreplaceable for parents, too.

Add comment